General De la Rey releases General Lord Methuen after his wounds are treated

8 March 1902

References

South African History Online, ‘Anglo-Boer War 2: Gen. De la Rey defeats and captures Gen. Methuen in the Battle of Tweebosch (or De Klipdrift) in Western Tran’ , [online] available at www.sahistory.org.za (Accessed: 13 February 2013)|

Boddy-Evans, A. ‘This Day in African History: 8 March’, from About African History, [online], available at africanhistory.about.com (Accessed: 13 February 2013)|

Melrose House, ‘The Guerrilla War, Part 3’, [online], available at www.melrosehouse.co.za (Accessed: 13 February 2013)

Towards the end of the Second South African War (Anglo-Boer War 2), General De La Rey released General Lord Methuen after his wounds were treated. After only travelling 29 kilometres Methuen's party was once again taken - De La Rey had been forced to reverse his decision by the burghers of his Commando. General Methuen was defeated and captured by General De La Rey on 7 March 1902 in the Battle of Tweebosch (or De Klipdrift), Western Transvaal. This was the last important battle won by the Boer forces. Methuen and more than 870 soldiers were captured.

General De la Rey protests British mistreatment of women and children

16 August 1901

References

Wessels. A.c., "General De la Rey protests British mistreatment of women and children",from women24,[Online], available at blogs.women24.com [Accessed: 14 August 2013]| Anglo-Boer War. [online] Available at: angloboerwar.com [Accessed 4 August 2009]

The Anglo-Boer War broke out in 1899 and was the result of the British annexation of the Transvaal, soon after gold had been discovered in the region in 1886. The Boers made use of guerrilla tactics by sabotaging British supply wagons, while the British responded by burning down the farms that the Boers received their supplies from. This was known as the scorched earth policy and resulted in the destruction of over 30 000 Boer farm houses. Boer women and children, as well as their black servants, were taken to concentration camps, where they were met with appalling conditions, malnutrition, diseases and in many instances, death. The scorched earth policy had been implemented by March 1901. On 16 August 1901, De la Rey, a Boer general, had protested against the inhumane conditions to which women and children in the camps were being exposed. This cause was taken up by Emily Hobhouse, who campaigned for the closure of concentration camps and collected clothing, supplies and money to support Boer families at the end of the war. Around 26 000 Boer women and children, as well as 15 000 black people, died in concentration camps during the course of the Anglo-Boer War. The Treaty of Vereeniging, signed in May 1902, brought the closure of the concentration camps and an end to the inhumane treatment of Boer women and children at the hands of the British. Related: The Rise of Afrikaner Nationalism

Anglo-Boer War 2: The Battle of Enslin or Graspan takes place, with the burghers under General De la Rey and Commandant Lubbe

Anglo-Boer War 2 -ZAR General De la Rey arrests ex-General Schoeman on his farm near Pretoria for refusing to obey an order to

General De la Rey protests the British mistreatment of women and children.

National Party (NP)

The first leader of the National Party (NP) became Prime Minister as part of the PACT government in 1924. The NP was the governing party of South Africa from 1948 until 1994, and was disbanded in 2005. Its policies included apartheid, the establishment of a South African Republic, and the promotion of Afrikaner culture. NP members were sometimes known as ‘Nationalists’ or ‘Nats’.

The feature includes a history of the National party, broken down into sections, according to significant periods of the NP’s history. An archive section listing and linking to relevant speeches, articles, documents and interviews. Featured is also a people section that lists all of the key figures and members of the NP, with links to their relevant biographies.

A history of the National Party

Founding and ideology (1910-1914)

In 1910 the Union of South Africa was established, and the previously separate colonies of the Cape, Natal, Transvaal and the Orange Free State became provinces in the Union. However, the union was established with dominion status, which effectively meant that South Africa was no longer a colony, but it was not independent and could not leave the empire or ignore the monarchy. After the 1910 elections Louis Botha became the first prime minister of the Union, and headed the South African Party (SAP) - an amalgam of Afrikaner parties that advocated close cooperation between Afrikaners and persons of British descent.

The founder of the NP, General JBM Hertzog, was a member of the Union Government, and was fiercely and publicly nationalistic. This offended English-speaking South Africans and stood in opposition to Botha’s policies of national unity. However, many Afrikaans people saw Hertzog as their representative and many important Afrikaans political and cultural leaders supported him- particularly people from the Orange Free State and the Cape. Hertzog often publicly disagreed with the opinions of his fellow leaders of the SAP, in particular, those of Prime Minister Louis Botha and General Jan Smuts. He promoted South Africa’s interests above Britain’s and saw English and Afrikaans South Africans developing in two parallel, but separate, cultural streams. Some enthusiastic supporters of the British Empire’s presence in South Africa described him as anti-British, and called for his removal from government. Some even decided to resign rather than work with him- while he refused to leave his position.

In May 1913, his Orange Free State supporters in the SAP insisted on his inclusion in the cabinet at the SAP Free State Congress, while the Transvaal members who supported Botha thought he should be excluded. At the national SAP Congress in November 1913, in Cape Town, Botha won enough support to keep Hertzog out of the cabinet. This was the last straw for Hertzog and he left the SAP to form the National Party.

From 1 to 9 January 1914, Hertzog’s supporters met in Bloemfontein to form the National Party, and to lay down its principles. The main aim was to direct the people’s ambitions and beliefs along Christian lines towards an independent South Africa. Political freedom from Britain was essential to the NP, but the party was prepared to maintain the current relationship with the Empire. They also insisted on equality of the two official languages, English and Dutch. Since Hertzog’s policies were orientated towards Afrikaner nationalism, most of his supporters were Afrikaans people.

On 1 July 1914 the National Party of the Orange Free State was born and on 26 August the Transvaal followed. The Cape National Party was founded on 9 June 1915.

The NP did not have a regular mouthpiece to promote its policies and campaigns like the SAP’s Ons Land newspaper in Cape Town and De Volkstem in Pretoria. Die Burger newspaper was therefore created in the Cape on 26 July 1915 for this specific purpose, with D. F. Malan as editor.

The National Party strengthens (1914-1923)

Most Afrikaners were against South African participation in World War 1 on the side of the British. Therefore, when South Africa was asked to invade German South West Africa (SWA) in August 1914 there was opposition from the ranks of the newly formed National Party (NP), and even from some who were part of the South African government. At their August congress the opposed invasion, and on 15 August there was a republican demonstration in Lichtenburg. Besides these protest efforts, it was agreed that South West Africa should be invaded.

The economic depression after the war and dissatisfaction from Black South Africans and other extra-parliamentary groups made the SAP's rule more difficult. The main reason for black anger was Smuts' acceptance of the Stallard report that stated:

”It should be a recognised principle that natives (men, women and children) should only be permitted within municipal areas in so far and for as long as their presence is demanded by the wants of the white population. The masterless native in urban areas is a source of danger and a cause of degradation of both black and white. If the native is to be regarded as a permanent element in municipal areas there can be no justification for basing his exclusion from the franchise on the simple ground of colour.” (This report later led to the passing of the Natives (Urban Areas) Act no 21 of 1923).

The Afrikaner opposition to WW1 proved to strengthen the, particularly after the death of General De la Rey (Afrikaners blamed Smuts and Botha). The death of General Louis Botha in 1919 pushed away more of the SAP supporters, and by the end of the Great War many of the SAP’s supporters had left the party and joined the.

In the 1920 elections it became clear that the SAP would need the cooperation to form a combined cabinet, in order to maintain political stability. Members of both parties met at Robertson on 26 and 27 May 1920, and made a potential agreement. On 22 September the two parties met again, but they could not finalize an agreement. The main point of disagreement concerned South Africa’s relationship with Britain - Hertzog wanted independence, while Smuts was happy with the situation as it was.

The Rand Rebellion of 1922 further strengthened the popularity, as it led to cooperation between the and the Labour Party (LP). The Rebellion was the result of severe labour unrest that had been simmering for some time. Both parties wanted to protect White labour, and decided to make a pact in April 1923 that would ensure that they would not oppose each other in the elections, and would support each other’s candidates in certain areas. This Pact resulted in the defeat of the SAP in the 27 June 1924 general elections. Afrikaans then became an official language and the country got a new flag.

The Pact Government (1924-1938)

After the Pact Government's 1924 election victory, South Africa had a new government. Hertzog was Prime Minister and also Minister of Native Affairs. His chief assistants were Tielman Roos (the leader of the National Party in the Transvaal), who was Deputy Prime Minister, and Minister of Justice. Dr D. F. Malan, who was the leader of the NP in the Cape, and became Minister of the Interior, Public Health and Education. Hertzog's close confidant, N. C. Havenga of the Orange Free State was made Minister of Finance. To express his gratitude to the Labour Party (for their help in getting him into power) Hertzog included two English-speaking Labour Party men in his cabinet, namely Colonel F. H. P. Creswell, as Minister of Defence, and T. Boydell, as Minister of Public Works, Posts and Telegraphs.

The Hertzog government curtailed the electoral power of non-Whites, and furthered the system of allocating “reserved” areas for Blacks as their permanent homes- while regulating their movements in the remainder of the country.

In 1926 South Africa’s position in relation to Britain was made clear in the Balfour Declaration, drawn up at the Imperial Conference of the same year. The Declaration became a law in 1931 with the Statute of Westminster, and the Pact Government’s greatest progress was made in industrial legislation and economy. Its protection of White workers and strict control over industry removed all problems in mines and factories, and these industries grew enormously .

The Pact Government managed to keep the white voters happy, and five years later in the 1929 election, they were able to win again - therefore securing a second term, from 1929 to 1934. After the 1929 election Hertzog still gave his Pact partner, the LP, some representation in the new cabinet - with Colonel F. H. P. Creswell keeping the portfolios of Defence and Labour, while H. W. Sampson was named Minister of Posts and Telegraphs. The rest of the cabinet was made up of NP members, who gradually laid more and more stress on republican independence and Afrikaner identity.

The Great Depression, from 1930 to 1933, made the government’s rule difficult. Britain left the gold standard on 21 September 1931, and Tielman Roos returned to politics in 1932 to oppose Hertzog in his position to retain the gold standard. His campaign was successful and the government met their demand.

Over time, the difference between the NP and SAP became smaller, and in 1933 the two parties merged to form a coalition government. The two parties were named the United Party (UP) in 1934, but D. F. Malan and his Cape NP refused to join. He remained independent to form the new opposition, which was called the Purified National Party (PNP).

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 caused an internal split in the UP. Hertzog wanted to remain neutral in the war and by winning a crucial vote in parliament (September 1939), Smuts became prime minister again and brought South Africa into the war on the British (Allied) side. Hertzog then returned to the NP, which was reformed as the Herenigde Nasionale Party (HNP) [Reformed National Party] on 29 Jan 1940. Hertzog was the party’s leader, with Malan as his deputy.

NP Ascendancy and Apartheid (1939-1950s)

The split decision in 1939 to take South Africa into the war, and the disruption the war effort, caused Afrikaners to be seriously alienated from the UP. By 1948 there was growing irritation with wartime restrictions that were still in place, and living costs had increased sharply. White farmers in the northern provinces were particularly unhappy that Black labourers were leaving farms and moving to the cities, and therefore demanded the strict application of pass laws.

In the election of 26 May 1948, D.F. Malan's National Party, in alliance with N.C. Havenga's Afrikaner Party, won with a razor-thin majority of five seats and only 40% of the overall electoral vote. The alliance was formed during the war from General Hertzog's core support

Malan said after the election: “Today South Africa belongs to us once more. South Africa is our own for the first time since Union, and may God grant that it will always remain our own.” When Malan said that South Africa “belonged” to the Afrikaners he did not have the white-black struggle in mind, but rather the rivalry between the Afrikaner and the English community.

After the 1948 election, The NP that came to power was effectively two parties rolled into one. The one was a party for white supremacy that introduced apartheid and promised the electorate that it would secure the political future of whites; the other was a nationalist party that sought to mobilise the Afrikaner community by appealing to Afrikaans culture i.e. their beliefs, prejudices and moral convictions- establishing a sense of common history, and shared hopes and fears for the future.

Immediately after the 1948 election, the government began to remove any remaining symbols of the historic British ascendancy. It abolished British citizenship and the right of appeal to the Privy Council (1950). It scrapped God Save the Queen as one of the naÂtional anthems, removed the Union Jack as one of the national ensigns (1957) and took over the naval base in Simon's Town from the Royal Navy (1957). The removal of these symbols of dual citizenship was seen as a victory for Afrikaner nationalism.

The NP's advance was the story of a people on the move, filled with enthusiasm about the 'Afrikaner cause'- putting their imprint on the state, defining its symbols, and giving their schools and universities a pronounced Afrikaans character. Political power steadily enhanced their social self-confidence. In the world of big business Rembrandt, Sanlam, Volkskas and other Afrikaner enterprises soon began to earn the respect of their English rivals.

However, apartheid policy steadily marginalised ethnic groups, and undermined their culture of and pride in their achievements. For others it seemed as if the Afrikaners were obsessed with fears about their own survival, and did not care about the damage and the hurt that apartheid inflicted upon others in a far weaker position.

The novelist Alan Paton made this comment about Afrikaner nationalism: “It is one of the deep mysteries of Afrikaner nationalist psychology that a Nationalist can observe the highest standards toÂwards his own kind, but can observe an entirely different standard towards others, and more especially if they are not White.”

Malan was prime minister from 1948 to 1954, and was directly succeeded by J.G. Strijdom as leader and prime minister. This signalled the new dominance of the Transvaal in the NP caucus. Later, in the 1958 election, the NP won 103 seats and the UP just 53, with H. F. Verwoerd elected as the new Prime Minister.

The elected government greatly strengthened white control of the country, and apartheid rested on several bases. The most important were the restriction of all power to Whites, racial classification and racial sex laws. Laws also allocated group areas for each raÂcial community, segregated schools and universities, and eliminated integrated public facilities and sport. Whites were protected in the labour market, and a system of influx control that stemmed from Black urbanization lead to the creation of designated 'homelands' for Blacks. This was the basis for preventing them from demanding rights in the common area (timeline of Apartheid legislation).

Black South Africans had long protested their inferior treatment through organizations such as the African National Congress (ANC; founded in 1912) and the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union of Africa (founded 1919 by Clements Kadalie). In the 1950s and early 1960s there were various protests against the National Party's policies, involving passive resistance and the burning of passbooks. In 1960, a peaceful anti- pass law protest in Sharpeville (near Johannesburg) ended when police opened fire, massacring 70 protesters and wounding about 190 others. This protest was organized by the Pan-Africanist Congress (an offshoot of the ANC). In the 1960s most leaders (including ANC leaders Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu) who opposed apartheid were either in jail or living in exile, while the government proceeded with its plans to segregate blacks on a more permanent basis. (Liberation Struggle in the 1960s).

What the 1948 government meant to the English-speaking White population?

While retaining their economic dominance, English-speakers continued to hold the key to future domestic fixed investment, and to foreign fixed investment. By 1948 the per capita income of English-speakers was more than double that of Afrikaners, and their level of eduÂcation was much higher. They also identified with a culture that was vastly richer and more diverse than Afrikaans culture.

After the 1948 election the English community in South Africa found itself in the political wilderness. Patrick Duncan, son of a South African governor-general, wrote: “English South Africans are today in the power of their adversaries. They are the only English group of any size in the world today that is, and will remain for some time, a ruled, subordinated minority. They are beginning to know what the great majority of all South Africans have always known - what it is to be second-class citizens in the land of one's birth.”

For English-speaking business leaders, the NP victory came as a major shock, as the Smuts government had been ideal for English business. After 1948, English business leaders contributed substantially to the United South African Trust Fund that funded the UP- with a view to unseating the NP government. Ernest Oppenheimer, the magnate controlling the giant conglomerate Anglo American Corporation, was the main donor. However, business was hardly liberal, and this fund refused to back the Liberal Party that Alan Paton had helped to form after the 1953 election - which propagated a programme of a multi-racial democracy based on universal franchise.

By the mid-1950s, English business leaders were beginning to accept the status quo, and were working with the government. Manufacturers enthusiastically welcomed the government's policy of promoting growth and boosting import substitution through protection. Mining magnates reaped the benefits of a very cheap, docile labour force, while blaming the government for the system.

International reactions to the results of the 1948 election and the introduction of apartheid

The result of the 1948 election dismayed Britain, South Africa's principal foreign investor and trading partner. But with the shadow of the Cold War falling over the world, the priority for Western governments was to prevent South Africa, with its minerals and strategic location, from falling under communist influence. The British Labour government under Clement Attlee concluded that this aspect was more important than its revulsion for apartheid. He would soon offer South Africa access to the intelligence secrets of Britain and the United States.

In the southern states of America, segregation still held sway. A survey in 1942 found that only 2% of whites favoured school integration, only 12% residential integration, and only one-fifth thought the intelligence of blacks was on the same level as that of whites. Even among northern whites only 30-40% supported racial integration.

The West did not insist on a popular democracy in South Africa, arguing that such a system was impossible for the time being. During the 1950s it was not uncommon for Western leaders to express racist views. In 1951 Herbert Morrison, foreign secretary in the British Labour government, regarded independence for African colonies as comparÂable to “giving a child often a latch-key, a bank account and a shotgun”.

Still, the defeat of Nazi Germany and the horror of the Holocaust had discredited racial ideologies, and speeded up pressure for racial integration, particularly in the United States. The granting of independence to India in 1947 was a major turning point in world history that intensified the pressure to grant subordinated ethnic groups their freedom. The General Assembly of the United Nations became an effective platform for the nations of the Third World to vent their anger over centuries of Western domination, and apartheid soon became the focus of their wrath.

The Republic of South Africa and Racial Strife (1960-1984)

One of these goals was achieved in 1960, when the White population voted in a referendum to sever South Africa's ties with the British Monarchy, and establish a republic. On 5 October 1960 South African whites were asked: “Do you support a republic for the Union?”. The result showed just over 52 per cent in favour of the change.

The opposition United Party actively campaigned for a “No” vote, while the smaller Progressive Party appealed to supporters of the proposed change to “reject this republic”, arguing that South Africa's membership of the Commonwealth, with which it had privileged trade links, would be threatened.

The National Party had not ruled out continued membership after the country became a republic, but the Commonwealth now had new Asian and African members who saw the apartheid regime's membership as an affront to the organisation's democratic principles. Consequently, South Africa left the Commonwealth on becoming a republic.

When the Republic of South Africa was declared on May 31, 1961, Queen Elizabeth II ceased to be head of state, and the last Governor General of the Union took office as the first State President. Charles Robberts Swart, the last Governor-General, was sworn in as the first State President (see “People”section for more detail about this position).

The State President performed mainly ceremonial duties and the ruling National Party decided against having an executive presidency, instead adopting a minimalist approach - a conciliatory gesture to English-speaking whites who were opposed to a republic. Like Governor-Generals before them, State Presidents were retired National Party ministers, and consequently, white, Afrikaner, and male. Therefore, HF Verwoerd remained on as the Prime Minister of the country.

In 1966, Prime Minister Verwoerd was assassinated by a discontented White government employee, and B.J. Vorster became the new Prime Minister. From the late 1960s, the Vorster government began attempts to start a dialogue on racial and other matters with independent African nations. These attempts met with little success, except for the establishment of diplomatic relations with Malawi and the adjacent nations of Lesotho, Botswana, and Swaziland - all of which were economically dependent on South Africa.

South Africa was strongly opposed to the establishment of Black rule in the White-dominated countries of Angola, Mozambique, and Rhodesia, and gave military assistance to Whites there. However, by late 1974, with independence for Angola and Mozambique under majority rule imminent, South Africa faced the prospect of further isolation from the international community - as one of the few remaining White-ruled nations of Africa. In the early 1970s, increasing numbers of whites (especially students) protested apartheid, and the National party itself was divided, largely on questions of race relations, into the somewhat liberal verligte [Afrikaans=enlightened] faction and the conservative verkrampte [Afrikaans,=narrow-minded] group.

In the early 1970s, black workers staged strikes and violently revolted against their inferior conditions. South Africa invaded Angola in 1975 in an attempt to crush mounting opposition in exile, but the action was a complete failure. In 1976, open rebellion erupted in the black township of Soweto, in protest against the use of Afrikaans as the medium of instruction in Black schools. Over the next few months, rioting spread to other large cities of South Africa, which resulted in the deaths of more than 600 Black people. In 1977, the death of Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko in police custody (under suspicious circumstances) prompted protests and sanctions.

The National Party increased its parliamentary majority in almost every election between 1948 and 1977, and despite all the protest against apartheid, the National Party got its best-ever result in the 1977 elections with support of 64.8% of the White voters and 134 seats in parliament out of 165.

Pieter Willem Botha became prime minister in 1978, and pledged to uphold apartheid as well as improve race relations. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the government granted “independence” to four homelands: Transkei (1976), Bophuthatswana (1977), Venda (1979), and Ciskei (1981). In the early 1980s, as the regime hotly debated the extent of reforms, Botha began to reform some of the apartheid policies. He legalised interracial marriages and multiracial political parties, and relaxed the Group Areas Act.

In 1984, a new constitution was enacted which provided for a Tricameral Parliament. The new Parliament included the House of Representatives, comprised of Coloureds; the House of Delegates, comprised of Indians; and the House of Assembly, comprised of Whites. This system left the Whites with more seats in the Parliament than the Indians and Coloureds combined. Blacks violently protested being shut out of the system, and the ANC and PAC, both of whom had traditionally used non-violent means to protest inequality, began to advocate more extreme measures (Umkhonto we Sizwe and the turn to the armed struggle).

Regime Unravels (1985-1991)

As attacks against police stations and other government installations increased, the regime announced an indefinite state of emergency in 1985. In 1986, Anglican Bishop Desmond Tutu, a black South African leader opposing apartheid, addressed the United Nations and urged further sanctions against South Africa. A wave of strikes and riots marked the 10th anniversary of the Soweto uprising in 1987.

In 1989, in the midst of rising political instability, growing economic problems and diplomatic isolation, President Botha fell ill and was succeeded, first as party leader, then as president, by F. W. de Klerk. Although a conservative, de Klerk realised the impracticality of maintaining apartheid forever, and soon after taking power, he decided that it would be better to negotiate while there was still time to reach a compromise, than to hold out until forced to negotiate on less favourable terms. He therefore persuaded the National Party to enter into negotiations with representatives of the Black community.

Late in 1989, the National Party won the most bitterly contested election in decades, pledging to negotiate an end to the apartheid system that it had established. Early in 1990 de Klerk's government began relaxing apartheid restrictions. The African National Congress (ANC) and other liberation organisations were legalized and Nelson Mandela was released after twenty-seven years of imprisonment.

In late 1991 the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA), a multiracial forum set up by de Klerk and Mandela, began efforts to negotiate a new constitution, and a transition to a multiracial democracy with majority rule. In March 1992, voters endorsed constitutional reform efforts by a wide margin in a referendum open only to Whites. However, there was continued violent protests from opponents of the process, especially by supporters of Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, leader of the Zulu-based Inkatha movement - with the backing and sometimes active participation of the South African security forces.

The New South Africa and the New National Party (1993-2005)

Despite obstacles and delays, an interim constitution was completed in 1993. This ended nearly three centuries of white rule in South Africa, and marked the eradication of white-minority rule on the African continent. A 32-member multiparty transitional government council was formed with blacks in the majority, and in April 1994, days after the Inkatha Freedom party ended an electoral boycott, the republic's first multiracial election was held. The ANC won an overwhelming victory, and Nelson Mandela became president. South Africa also rejoined the Commonwealth in 1994 and relinquished its last hold in Namibia, by ceding the exclave of Walvis Bay.

In 1994 and 1995, the last vestiges of apartheid were dismantled, and a new national constitution was approved and adopted in May 1996. It provided for a strong presidency and eliminated provisions guaranteeing White-led and other minority party representation in the government. De Klerk and the National party supported the new charter, despite disagreement over some provisions. Shortly afterward, de Klerk and the National party quit the national unity government to become part of the opposition- the New National party after 1998. The new government faced the daunting task of trying to address the inequities produced by decades of apartheid, while promoting privatization and a favourable investment climate.

The liberal Democratic party became the leading opposition party, and in 2000 it joined forces with the New National Party to form the Democratic Alliance (DA). That coalition, however, survived only until late 2001, when the New National party left to form a coalition with the ANC.

Parliamentary elections in April 2004, resulted in a resounding victory for the ANC, which won nearly 70% of the vote, while the DA remained the largest opposition party and increased its share of the vote. The new parliament subsequently re-elected President Mbeki. As a result of its poor showing, the New National party merged with the ANC, and voted to disband in April 2005.

Further Reading

-

What won the NP the 1948 election? by Hermann Giliomee, PoliticsWeb, 22 October 2020

… parties that advocated close cooperation between Afrikaners and persons of British descent. The founder of the NP, General JBM Hertzog, was a member of the Union Government, and was fiercely and publicly nationalistic. This offended … did not have a regular mouthpiece to promote its policies and campaigns like the SAP’s Ons Land newspaper in Cape Town and De Volkstem in Pretoria. Die Burger newspaper was therefore created in the Cape on 26 July 1915 for this specific purpose, … Act no 21 of 1923). The Afrikaner opposition to WW1 proved to strengthen the, particularly after the death of GeneralDelaRey (Afrikaners blamed Smuts and Botha). The death of General Louis Botha in 1919 pushed away more of the SAP supporters, …

Christiaan Rudolf De Wet

Christiaan de Wet was born at Leeuwkop near Smithfield, Orange Free State, on 7 October 1854. He received little formal education, spending his days helping his father in the management of the farm Nuwejaarsfontein, near the present town of Dewetsdorp. At the age of nineteen, he married Cornelia Margaretha Kruger, a woman of strong character. They were to have sixteen children. Upon the annexation of the Transvaal in 1877, he moved to the Vredefort district in the Orange Free State, then to Weltevreden near the present village of Koppies, and from there to Rietfontein in the Heidelberg district (Transvaal), in 1880.

De Wet was twenty-seven when the First Anglo-Boer War broke out in 1880. He fought with the Heidelberg Commando, taking part in the Battle of Laing's Nek, where he displayed courage at Ingogo and in the storming of Majuba in early 1881. After the war and the restoration of Transvaal independence, he was elected a veld-cornet. In 1882, the family moved again, this time to the farm Suikerboskop in the Lydenburg district. Elected to the Transvaal Volksraad in 1885, he only attended one session because he decided to buy his father's farm, Nuwejaarsfontein, and the family moved back to the Orange Free State. In 1896, he was to move once more, this time to the farm Rooipoort in the Heilbron district. In 1889, he was elected to the Free State's Volksraad and represented Upper Modder River until 1898.

Expecting the outbreak of war in 1899, De Wet, then forty-five, prepared for the hardships to come. Among other things, he bought Fleur, the white Arab horse that was to carry him steadfastly through many battles and across thousands of miles on the veld. On 2 October 1899, De Wet and his eldest son, Kotie, were called up as ordinary burghers in the Heilbron commando. De Wet's sons, Izak and Christiaan enlisted as volunteers and the four of them reported for duty under Commandant Lucas Steenekamp.

In March and April 1900 De Wet launched an offensive that heralded the Boer revival. Attacking south-eastwards, in the guerrilla style for which he was to become legendary.

In order to decide whether to continue the war or to accept the British terms the Boer leaders called a conference of sixty representatives of the Transvaal and Orange Free State to be held at Vereeniging on 15 May. With Steyn ill, De Wet, as Acting President, represented the Free State. De Wet said he was prepared to carry on the struggle beside President Steyn to the bitter end. The Treaty of Vereeniging was the result of the Boer discussions.

With his family, De Wet returned to his ruined farm, Rooipoort. In July 1902, leaving his wife and children in a tent on the farm, he left for Europe with Botha and De la Rey to try to raise funds for the widows and orphans impoverished by the war. On board ship, the Reverend J D Kestell assisted him in the prodigious effort of writing his war memoirs, De Strijd Tusschen Boer en Brit (subsequently published in English as Three Years War). The book was an overwhelming success and was later translated into at least six languages.On his return, De Wet played an important part in the movement to counter Milnerism in the Free State, which culminated in the establishment of the Orangia Unie in 1906. When the Orange River Sovereignty was granted self-Government in 1907, De Wet was elected the member for Vredefort and became Abraham Fischer's Minister of Agriculture. He was a delegate to the National Convention of 1908-09, which met to decide on the Constitution of the Union of South Africa. He left politics after Union in 1910 and went to live at Allanvale, near Memel, where he was nominated to the Union Defence Board. A supporter of Hertzog, his fiery personality came to the fore when he made his famous 'dunghill' speech in Pretoria on 28 December 1912. The following year he resigned from the Defence Board. In 1914, when De Wet and Hertzog founded the National Party, the political divisions between Afrikaners grew wider.

In mid-August 1914, a number of prominent Boer War leaders were in contact with each other. They were: General de la Rey, now a Government senator, Lieutenant-Colonel 'Manie' Maritz, who was in command of the Union forces near the border of South West Africa, General Beyers, the commander of the Active Citizen Force, General Kemp, the commander of the Potchefstroom military camp, and General De Wet. Wanting no part in 'England's wars', they opposed South African participation in World War I and the proposed invasion of German South West Africa by South African forces. According to subsequent statements of the participants, these leaders saw an opportunity of regaining the independence they had so dearly lost twelve years earlier and were planning a coup d'etat, which was to take place on the South West African border, in the Free State and at Potchefstroom. Beyers had arranged to meet Governor Seitz of German South West Africa at the border. De la Rey was to address the soldiers in the camp at Potchefstroom. And Maritz was to defect to the Germans with his men. Beyers and Kemp both resigned their commissions. On 15 September Beyers set out to drive to Potchefstroom with General J.H. de la Rey. When they failed to stop at a roadblock at Langlaagte, a trooper opened fire and De la Rey was shot dead. After speaking at De la Rey's funeral in Lichtenburg, De Wet took part in a protest meeting in the town the following day. It was decided that he and others would try to persuade Botha and Smuts to abandon their plans to attack German South West Africa. But the deputation achieved nothing.

Soon after De la Rey's funeral, Maritz defected to the German side with more than a thousand men. Kemp joined him. At Steenbokfontein on 29 October 1914, Beyers issued a declaration on behalf of himself and De Wet that they were to stage an armed protest. Afrikaners flocked to them, intending to march on Pretoria. The rebellion spread, inspired by De Wet who occupied towns and seized property in the north-eastern Free State where he commanded a great following. In total, more than 11,400 poorly equipped men rebelled. They were doomed to failure.

Martial law was declared and Government troops were swiftly mustered to suppress the revolt. It took Botha one month. At Allemanskraal, De Wet's son Danie and several other rebels were killed. De Wet, who was grieving bitterly over his son, occupied Winburg. At Mushroom Valley, north-east of Bloemfontein, Botha completely surprised the poorly armed rebels. A short sharp skirmish showed they were no match for Botha and the Government troops. Twenty-two rebels and six of Botha's men were killed; the rest were captured or fled in every direction.

With his family, De Wet returned to his ruined farm, Rooipoort. In July 1902, leaving his wife and children in a tent on the farm, he left for Europe with Botha and De la Rey to try to raise funds for the widows and orphans impoverished by the war. On board ship, the Reverend J D Kestell assisted him in the prodigious effort of writing his war memoirs, De Strijd Tusschen Boer en Brit (subsequently published in English as Three Years War). The book was an overwhelming success and was later translated into at least six languages. On his return, De Wet played an important part in the movement to counter Milnerism in the Free State, which culminated in the establishment of the Orangia Unie in 1906. When the Orange River Sovereignty was granted self-Government in 1907, De Wet was elected the member for Vredefort and became Abraham Fischer's Minister of Agriculture. He was a delegate to the National Convention of 1908-09, which met to decide on the Constitution of the Union of South Africa. He left politics after Union in 1910 and went to live at Allanvale, near Memel, where he was nominated to the Union Defence Board. A supporter of Hertzog, his fiery personality came to the fore when he made his famous 'dunghill' speech in Pretoria on 28 December 1912. The following year he resigned from the Defence Board. In 1914, when De Wet and Hertzog founded the National Party, the political divisions between Afrikaners grew wider 1, 400 poorly equipped men rebelled. They were doomed to failure.

Ever the master of evasive tactics, De Wet managed to escape, only to be engaged in a fierce skirmish at Virginia station. Seeing it was useless to continue the fight, he instructed his burghers to accept Botha's favourable amnesty terms, while he and a handful of faithful followers headed towards the Kalahari Desert in a bid to join Maritz in South West Africa.

On 30 November 1914, at Waterbury farm near Vryburg, an informer told Colonel G F Jordaan that the exhausted De Wet and his companions were hiding out in the district. Coen Brits set off after him with a posse of motorcars.

For the first time in his life, De Wet was taken prisoner. "It was the motorcars that beat me," he said. And on hearing that his captors were Afrikaners, he remarked with a wry smile, "Well, thank God for that. Then the English never captured me!"

De Wet was taken at once to the Johannesburg Fort, where together with other rebels he was imprisoned. Special courts were set up to try the rebels. De Wet got six years and a fine of £2,000. He expressed surprise at the leniency of his sentence. Within a short time the fine was collected from voluntary contributions, and after six months he was granted a reprieve. But imprisonment had seriously undermined his health.

Shortly after his release, De Wet sold his farm Allanvale and settled near Edenburg for a few years. Then he moved for the last time to the farm Klipfontein, near Dewetsdorp. Although he was poor and a shadow of his former self, his spirit remained forceful; and an incessant flow of visitors found their way to his door to pay their respects to him. But, because of his illness, he made few public appearances. Nevertheless, when ex-President Steyn died in November 1916, De Wet paid tribute to his old friend and comrade-a-arms in a famous oration at the graveside. As he aged, De Wet became politically moderate, to the extent that he advised the inclusion of English-speaking citizens in political affairs; but he never forgave those who had collaborated during the Boer War

De Wet progressively weakened and at length, on 3 February 1922, he died on his farm. General Smuts, who had become Prime Minister, cabled his widow: 'A prince and a great man has fallen today.' De Wet was given a state funeral in Bloemfontein and buried next to President Steyn and Emily Hobhouse at the foot of the memorial to the women and children who died in the concentration camps. On the hundredth anniversary of his birth, a bronze equestrian statue, by Coert Steynberg, was unveiled at the Raadzaal in Bloemfontein.

Anglo-Boer War 2: The Battle of Silkaatsnek begins

11 July 1900

References

Cloete, P G (2000). The Anglo-Boer War: a chronology. ABC Press, Cape Town, pg 169.|

Wallis, F. (2000). Nuusdagboek: feite en fratse oor 1000 jaar, Kaapstad: Human & Rousseau).|

Kormorant, (2009), ‘The Battle of Silkaatsnek 11 July 1990 - ARMAGEDDON OF THE MOUNTAIN’, from Kormorant, 18 February [Online], Available at www.kormorant.co.za [Accessed: 10 July 2013]

There is a pass in the Magaliesberg known as Silkaatsnek It was here that the two 12-pounder guns of 'O' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery (RHA), were placed and ultimately captured in the first battle of Silkaatsnek on 11 July 1900. After the fall of Pretoria on 5 June 1900, the British forces found themselves in command of most strategic points, but with enormously extended lines of communication. In the then 'Western Transvaal', communications were maintained through huge tracts of inhospitable country, which were difficult to fight in; rough hills, tenacious bushes and hard stony ground with infrequent sources of water, especially in the southern winter. Conditions were ideal for guerrilla warfare conducted by tough, unsophisticated fighters who were brought up as horsemen and marksmen, who knew the country intimately and who could adapt themselves to harsh conditions using the topography to their advantage. 11 July 1900 marked the beginning of this type of war with four Boer actions, of which the action of Silkaatsnek was but one of three successes, with resultant timely encouragement to Boer morale in the Western Transvaal, and dismay amongst English garrisons and outposts. General De la Rey had commanded the northern sector of the Boer forces at Diamond Hill. After this battle, De la Rey, who also commanded the Western Transvalers, fell back to the Bronkhorstspruit-Balmoral area. On lO July, De la Rey was travelling north of Silkaatsnek towards Rustenburg with some 200 men, when his scouts brought information that the Nek was lightly held and that the commanding shoulders of the Nek had been ignored. He decided to attack. De la Rey launched a three-pronged attack on the small British force commanded by Colonel HR Roberts. De la Rey personally lead the frontal assault from the north and sent two groups of 200 men to scale both shoulders of the pass, where the British had placed small pickÂets. The burghers surrounded and captured two British field-guns, but the British put up a gallant fight that lasted the entire day. Colonel Roberts surrendered the next morning. 23 British troops were killed, Colonel Roberts and 44 others were wounded and 189 (including the wounded) were captured. The Boers casualties are unknown, but De la Rey's nephew and his adjutant were both killed, and a known 8 men were wounded. The Boers captured two field-guns, a machine gun, a numÂber of rifles ammunition. De la Rey used these weapons to rearm several burghers who returned to duty. Read SAHO's Anglo-Boer war feature.

Dwarsvlei, near Pretoria

The Farm Dwarsvlei is situated 15 kilometres North of Krugersdorp, on the road to Hekpoort, past Sterkfontein of Archaeological fame. It is still Owned and Farmed by Descendants of the Oosthuizen family, the Voortrekkers who first Settled there. It was the scene of at least two almost forgotten clashes between the Boers and the British during the Anglo-Boer War (1899 - 1902)

The first incident which took place here, on 11 July 1900, was a fierce Battle in which three Victoria Crosses were earned in circumstances initially remarkably similar to the Battle of Colenso, seven Months earlier, 15 December 1899. Amongst the Boer casualties was their Commander, Sarel Oosthuizen. The engagement was described by Major-General Smith-Dorrien as their 'most trying fight of the whole war'.

Then, on 9 October 1900, a captain in the Royal Scots Fusiliers, Hugh Montague Trenchard, was ambushed and critically wounded outside the door of the Farmhouse in the second incident which occurred on the Farm, during the War. Trenchard survived to become 'one of the few great men, who can be said to have changed the course of History'. He became 'the father of the Royal Air Force and the Architect of modern air power', dictating the role of Aerial Bombing Warfare in both the First and Second World Wars. He fought Economic cuts to keep the Air Force, in existence between the wars and it is said that, 'without him, there would have been no Battle of Britain'.

Today, only a short drive from Johannesburg, the tarred road to Hekpoort passes over the Battlefield of Dwarsvlei, but there is no indication of the events that took place there a Century ago. Not even a cartridge case remains to be seen, although the British alone fired 38 000 rounds that Day. The Farm and the Slope of the Witwatersberg to the North are now covered with invasive Wattle Trees, but the two Kopjes and the Hollow, beyond them remains open Veld, as it was a Century ago. Thus, the Panorama of the Battlefield can be easily surveyed. The positioning of the roads has changed slightly over time with the Hekpoort road to be to the West of the Kopjes, while the present tarred road follows the path between them taken by the guns.

The Battle of Dwarsvlei, 11 July 1900-

It was mid-Winter on the Highveld, Pretoria had fallen to the British, and General de la Rey had gathered the Burghers North of the Magaliesberg for the start of the guerrilla phase of the war. On that day, 11 July 1900, the British were engaged at four Places: Witpoort, East of Pretoria; Onderstepoort to the North; and Zilikat's Nek (Silkaatsnek) and Dwarsvlei in the West. The results of the actions at the last three sites was disastrous. The Gordon Highlanders and Shropshire Regiment under the Command of Major-General Smith-Dorrien were to leave Krugersdorp for Hekpoort in order to join the Scots Greys from Pretoria and link up with Baden-Powell at Olifantsnek, South of Rustenburg. The Force consisted of about 1 335 men, 597 Gordon Highlanders, 680 Shropshires, 34 Imperial Yeomanry with a Colt Gun, two Guns of the 78th Battery, three Ambulances and forty Wagons.

The Track they followed is in very much in the same position as the Tarred Road is today, topping a Rise after about 15 km before dropping through an open Hollow and rising again to cross the Witwatersberg beyond. Here the Boers, mainly from the Krugersdorp Commando under Sarel Oosthuizen, opened fire on them from the high ground.

The guns advanced between the two Kopjes to the open Ground and opened fire on the opposing Ridges while the Gordons took up positions on the Kopjes. As at Colenso, the Horse-Drawn Artillery, in their eagerness to come into action, had left the Infantry behind and found themselves in an exposed Position. They sent the limbers 600 Yards (548 metres) to the Rear, instead of taking advantage of the perfect cover provided by the Kopjes. The deadly Boer fire, from only 800 Yards (731 metres) away, soon took its toll and within half an hour, fourteen of the seventeen Gunners had been hit and the guns had been silenced. The section commander, Lieutenant Turner, although wounded three times, continued for some time to fire one of the guns himself. One of the limber teams, in endeavouring to remove a gun, had four horses shot and gave up the attempt, while the horses of the other had taken fright and bolted. Captain W E Gordon, with some Gordon Highlanders, then made a gallant but ultimately unsuccessful attempt to manhandle the guns. Captain D R Younger and three men were killed and seventeen were wounded in the attempt.

For his efforts, Captain Gordon was awarded the Victoria Cross, while Captain Younger's award was only gazetted on 8 August 1902, as Posthumous Awards were not made at the time. Corporal J F Mackay had been recommended for the Victoria Cross at Doornkop on 29 May 1900 as well as on three other occasions, including Dwarsvlei, where he had dashed out from the safety of the right Kopje, hoisted Captain Younger on his back, and carried him behind the left Kopje under the concentrated fire of several hundred rifles.

As the expected Scots Greys and two guns of the Royal Horse Artillery were pinned down and eventually Captured by De la Rey at Zilikat's Nek, Lord Roberts Signalled from Pretoria at 13.25 that the operation was to be cancelled and that the force must retire to Krugersdorp. Orders were issued for the withdrawal, but Lieutenant Turner, upon hearing of them from where he lay wounded next to the headquarters, burst out, 'Oh, you can't leave my guns!' Then, on Colonel Macbean's assurance that the Gordons could hold on all day, Smith-Dorrien cancelled the order.

Skirmishing continued for the rest of the Day and the Transport, HQ and Ambulance all came under fire. At dusk, the Boers, with shouts of 'Voorwaarts, mense, voorwaarts!' (Forward, people, forward!), attempted to capture the guns. They were driven off with considerable losses, including their leader, Sarel Oosthuizen. He was wounded in the thigh and Died a Month later, on 14 August 1900. The British guns were recovered and both sides withdrew from the Field, the British reaching Krugersdorp weary but in good spirits in the early Hours of the following Morning.

A week later, the British resumed their Mission, Reinforced by Lord Methuen's force, and passed the same Area on 19 July, observing a few Boers who kept their Distance and put up but slight resistance later.

In the Krugersdorp Cemetery, Captain Younger's Headstone stands thirty paces away from the Memorial stone to vecht-generaal Sarel Oosthuizen and his younger brother, korporaal Izak Johannes Oosthuizen (who died on 20 April 1902, a few days before the end of the war). The Battle of Dwarsvlei has also been referred to as: 'Leeuhoek, Door Boschfontein and Onrus', all being names of Farms in the Area, that the action took place in that day.

References

http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol113js.html

Further Reading

https://www.sahistory.org.za/.../anglo-boer-war-2-boer-general-sf-oosthuizen -dies-wounds-received-dwarsvlei-11-07-1900

https://www.sahistory.org.za/.../sterkfontein-caves-krugersdorp-within-cradle- humankind-world-heritage-site

https://www.sahistory.org.za/.../second-anglo-boer-war-1899-1902

https://www.sahistory.org.za/.../a-tribute-to-the-pioneers-voortrekkers-of-the- transvaal

https://www.sahistory.org.za/.../timeline-world-war-ii-1939-1945

https://www.sahistory.org.za/place/preller-rondawels-pelindaba

https://www.sahistory.org.za/place/krugersdorp

https://www.sahistory.org.za/place/kitson-steam-train-krugersdorp

Women and Children in White Concentration Camps during the Anglo-Boer War, 1900-1902

Due to the fact that Black People were detained in separate camps, the issue of Black Concentration Camps is dealt with in another chronology.

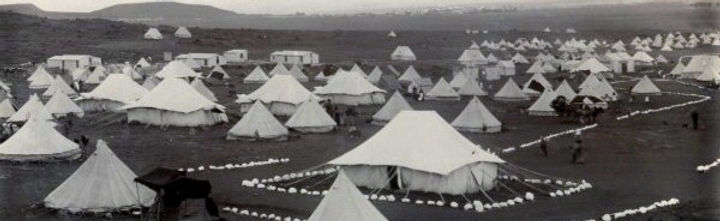

Boer women, children and men unfit for service were herded together in concentration camps by the British forces during Anglo-Boer War 2 (1899-1902). The first two of these camps (refugee camps) were established to house the families of burghers who had surrendered voluntarily, but very soon, with families of combatant burgers driven forcibly into camps established all over the country, the camps ceased to be refugee camps and became concentration camps. The abhorrent conditions in these camps caused the death of 4 177 women, 22 074 children under sixteen and 1 676 men, mainly those too old to be on commando, notwithstanding the efforts of an English lady, Emily Hobhouse, who tried her best to make the British authorities aware of the plight of especially the women and children in the camps.

1900

September, Major-Gen J.G. Maxwell announces that "... camps for burghers who voluntarily surrender are being formed at Pretoria and Bloemfontein." This signals the start of what was to evolve into the notorious Concentration Camp Policy.

22 September, As result of a military notice on this date, the first two 'refugee' camps are established at Pretoria and Bloemfontein. Initially the aim was to protect the families of burghers who had surrendered voluntarily and their families by the institution of these camps. As the families of combatant burghers were also driven into these and other camps, they ceased to be 'refugee' camps and became 'concentration' camps.

20 December, A proclamation issued by Lord Kitchener states that all burghers surrendering voluntarily, will be allowed to live with their families in Government Laagers until the end of the war and their stock and property will be respected and paid for.

21 December, Contrary to the announced intention, Lord Kitchener states in a memorandum to general officers the advantages of interning all women, children and men unfit for military services, also Blacks living on Boer farms, as this will be "the most effective method of limiting the endurance of the guerrillas... "The women and children brought in should be divided in two categories, viz.: 1st. Refugees, and the families of Neutrals, non-combatants, and surrendered Burghers. 2nd. Those whose husbands, fathers and sons are on Commando. The preference in accommodation, etc. should of course be given to the first class. With regard to Natives, it is not intended to clear ... locations, but only such and their stock as are on Boer farms."

Second Boer War - Bloemfontein Concentration Camp Image source

1901

21 January, Emily Hobhouse, an English philanthropist and social worker who tried to improve the plight of women and children in the camps, obtains permission to visit concentration camps. Lord Kitchener, however, disallows visits north of Bloemfontein.

24 January, Emily Hobhouse visits Bloemfontein concentration camps and is appalled by the conditions. Due to limited time and resources, she does not visit the camp for Blacks, although she urges the Guild of Loyal Women to do so.

30 January, Pushing panic-stricken groups of old men, women and children, crowded in wagons and preceded by huge flocks of livestock in front of them, French's drive enters the south-eastern ZAR (Transvaal).

31 January, Mrs Isie Smuts, wife of Gen. J.C. Smuts, is sent to Pietermaritzburg and placed under house arrest by the British military authorities, despite her pleas to be sent to concentration camps like other Boer women.Concentration camps have been established at Aliwal North, Brandfort, Elandsfontein, Heidelberg, Howick, Kimberley, Klerksdorp, Viljoensdrift, Waterfall North and Winburg.

25 February, A former member of the Free State Volksraad, H.S. Viljoen, and five other prisoners are set free from the Green Point Camp near Cape Town. They are sent to visit Free State concentration camps with the intention of influencing the women in the camps to persuade their husbands to lay down their arms. They are met with very little success.

27 February, Discriminatory food rations - 1st class rations for the families of 'hands-uppers' and 2nd class for the families of fighting burghers or those who refuse to work for the British - are discontinued in the 'Transvaal' concentration camps.

28 February, Concentration camps have been established at Kromellenboog, Middelburg, Norvalspont, Springfontein, Volksrust, and Vredefort Road.At the Middelburg conference between Supreme Commander Lord Kitchener and Commandant-General Louis Botha, Kitchener comments to Lord Roberts, now Commander-in Chief at the War Office in London: "They [referring to the Burghers S.K.] evidently do not like their women being brought in and I think it has made them more anxious for peace." The conference is discussing terms of a possible peace treaty.Sir Alfred Milner leaves Cape Town for Johannesburg to take up his duties as administrator of the 'new colonies'.

1 March, Concentration camps in the 'Orange River' and 'Transvaal' Colonies are transferred to civil control under Sir Alfred Milner.

4 March, Emily Hobhouse visits the Springfontein concentration camp.

6 March, Discriminatory food rations are also discontinued in the 'Orange River Colony' camps.

8 March, Emily Hobhouse visits the Norvalspont concentration camp.

12 March, Emily Hobhouse visits the Kimberley concentration camp.

6 April, Emily Hobhouse returns to Kimberley

9 April, Emily Hobhouse visits the Mafeking concentration camp.

12 April, Emily Hobhouse witnesses the clearing of Warrenton and the dispatch of people in open coal trucks.

13 April, Emily Hobhouse returns to Kimberley, witnessing the arrival of the people removed from Warrenton at the Kimberley camp, where there are only 25 tents available for 240 people.

20 April, The towns of Parys and Vredefort and many outlying farms have been cleared of inhabitants and supplies. The women and children have been removed to concentration camps.

21 April, Emily Hobhouse arrives in Bloemfontein.

23 April, Sir Alfred Milner refuses to issue a permit to Emily Hobhouse authorising her to travel north of Bloemfontein.

4 May, Emily Hobhouse arrives in Cape Town.

7 May, Emily Hobhouse leaves for Britain after an extended fact-finding tour of the concentration camps.

14 June, Speaking at a dinner party of the National Reform Union in England, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, leader of the Liberal opposition, says the war in South Africa is carried on by methods of barbarism.

17 June, David Lloyd-George in England condemns the concentration camps and the horrors inflicted on women and children in the camps in South Africa. He warns, "A barrier of dead children's bodies will rise between the British and Boer races in South Africa."

Emily Hobhouse tells the story of the young Lizzie van Zyl who died in the Bloemfontein concentration camp: She was a frail, weak little child in desperate need of good care. Yet, because her mother was one of the "undesirables" due to the fact that her father neither surrendered nor betrayed his people, Lizzie was placed on the lowest rations and so perished with hunger that, after a month in the camp, she was transferred to the new small hospital. Here she was treated harshly. The English disposed doctor and his nurses did not understand her language and, as she could not speak English, labeled her an idiot although she was mentally fit and normal. One day she dejectedly started calling for her mother, when a Mrs Botha walked over to her to console her. She was just telling the child that she would soon see her mother again, when she was brusquely interrupted by one of the nurses who told her not to interfere with the child as she was a nuisance. Quote from Stemme uit die Verlede ("Voices from the Past") - a collection of sworn statements by women who were detained in the concentration camps during the Second Boer War (1899-1902). Image source

18 June, Emily Hobhouse's report on concentration camps appear under the title, "To the S.A. Distress Fund, Report of a visit to the camps of women and children in the Cape and Orange River Colonies". Summarising the reasons for the high fatality rate, she writes, "Numbers crowded into small tents: some sick, some dying, occasionally a dead one among them; scanty rations dealt out raw; lack of fuel to cook them; lack of water for drinking, for cooking, for washing; lack of soap, brushes and other instruments of personal cleanliness; lack of bedding or of beds to keep the body off the bare earth; lack of clothing for warmth and in many cases for decency ..." Her conclusion is that the whole system is cruel and should be abolished.

26 June, Lord Kitchener, in a telegram to Milner: "I fear there is little doubt the war will now go on for considerable time unless stronger measures are taken ... Under the circumstances I strongly urge sending away wives and families and settling them somewhere else. Some such unexpected measure on our part is in my opinion essential to bring war to a rapid end."

27 June, The British War Department promises to look into Emily Hobhouse's suggestions regarding improvements to the concentration camps.

30 June, The official camp population is 85 410 for the White camps and the deaths reported for June are 777.

15 July, Dr K. Franks, the camp doctor at the Mafeking concentration camp reports that the camp is "overwhelmed" by 1 270 women and children brought in after sweeps on the western ZAR (Transvaal). Lack of facilities ads to the hardships encountered by the new arrivals.

16 July, The British Colonial Office announces the appointment of a Ladies Commission to investigate the concentration camps in South Africa. The commission, whose members are reputed to be impartial, is made up as follows:Chairlady Mrs Millicent G. Fawcett, who has recently criticised Emily Hobhouse in the Westminster Gazette; Dr Jane Waterson, daughter of a British general, who recently wrote against "the hysterical whining going on in England" while "we feed and pamper people who had not even the grace to say thank you for the care bestowed on them"; Lady Anne Knox, wife of Gen. Knox, who is presently serving in South Africa; Nursing sister Katherine Brereton, who has served in a Yoemanry Hospital in South Africa; Miss Lucy Deane, a government factory inspector on child welfare; Dr the Hon Ella Scarlett, a medical doctor. One of the doctors is to marry a concentration camp official before the end of their tour.

20 July, Commenting on confiscation of property and banishment of families, St John Brodrick, British secretary of State for War, writes to Kitchener: "... Your other suggestion of sending the Boer women to St Helena, etc., and telling their husbands that they would never return, seems difficult to work out. We cannot permanently keep 16,000 men in ring fences and they are not a marketable commodity in other lands ..."

25 July, Since 25 June, Emily Hobhouse has addressed twenty-six public meetings on concentration camps, raising money to improve conditions.

26 July, Emily Hobhouse again writes to Brodrick asking for reasons for the War Department's refusal to include her in the Ladies Commission. If she cannot go, "it was due to myself to convey to all interested that the failure to do so was due to the Government".

27 July, St John Rodrick replies to Emily Hobhouse's letter, "The only consideration in the selection of ladies to visit the Concentration Camps, beyond their special capacity for such work, was that they should be, so far as is possible, removed from the suspicion of partiality to the system adopted or the reverse."

31 July, The officially recorded camp population is 93 940 for the White camps and the deaths for July stands at 1 412.

16 August, General De la Rey protests to the British against the mistreatment of women and children.

20 August, Col. E.C. Ingouville-Williams' column transports Gen. De la Rey's mother to the Klerksdorp concentration camp. A member of the Cape Mounted Rifles notes in his diary: "She is 84 years old. I gave her some milk, jam, soup, etc. as she cannot eat hard tack and they have nothing else. We do not treat them as we ought to."

31 August, The officially recorded camp population for White camps is 105 347 and the camp fatalities for August stand at 1 878.

13 September, The Merebank Refugee Camp is established near Durban in an attempt to reduce the camp population in the Republics. Its most famous inmates are to be Mrs De Wet and her children.

30 September, Cornelius Broeksma is executed by an English firing squad in Johannesburg after having been found guilty of breaking the oath of neutrality and inciting others to do the same. A fund is started in Holland for his family and for this purpose a postcard with a picture of himself and his family is sold, bearing the inscription: "Cornelius Broeksma, hero and martyr in pity's cause. Shot by the English on 30th September 1901, because he refused to be silent about the cruel suffering in the women's camps."The officially recorded camp population of the White camps is 109 418 and the monthly deaths for September stand at 2 411.

1 October, Emily Hobhouse again urges the Minister of War, "in the name of the little children whom I have watched suffer and die" to implement improvements in the concentration camps.

26 October, As the commandoes in the Bethal district, Transvaal, become wise to Benson's night attacks, his success rate declines and he contents himself with 'ordinary clearing work' - burning farms and herding women, children, old men and other non-combatants with their livestock and vehicles.

27 October, Emily Hobhouse arrives in Table Bay on board the SS Avondale Castle, but is refused permission to go ashore by Col. H. Cooper, the Military Commandant of Cape Town.

29 October, Reverend John Knox Little states in the United Kingdom: "Among the unexampled efforts of kindness and leniency made throughout this war for the benefit of the enemy, none have surpassed the formation of the Concentration Camps".

31 October, Despite letters of protest to Lord Alfred Milner, Sir Walter Hely-Hutchinson and Lord Ripon, Emily Hobhouse, although unwell, is forced to undergo a medical examination. She is eventually wrapped in a shawl and physically carried off the Avondale Castle. She is taken aboard the Roslin Castle for deportation under martial law regulations.The officially recorded camp population of White camps is 113 506 and the deaths for October stand at 3 156.

1 November, Miss Emily Hobhouse, under deportation orders on board the Roslin Castle writes to Lord Kitchener: "... I hope in future you will exercise greater width of judgement in the exercise of your high office. To carry out orders such as these is a degradation both to the office and the manhood of your soldiers. I feel ashamed to own you as a fellow-countryman."And to Lord Milner: "Your brutal orders have been carried out and thus I hope you will be satisfied. Your narrow incompetency to see the real issues of this great struggle is leading you to such acts as this and many others, straining [staining S.K.] your own name and the reputation of England..."

Boer prisoners in Johannesburg. Source: Parliament Archive, Cape Town

7 November, The Governor of Natal informs St John Brodrick that the wives of Pres. Steyn, General Paul Roux, Chief Commandant C.R. de Wet, Vice President Schalk Burger and Gen. J.B.M. Hertzog, the last four all presently in Natal, are to be sent to a port, other than a British port, outside South Africa.Lord Milner, referring to the concentration camps, writes to British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain: "I did not originate this plan, but as we have gone so far with it, I fear that a change now might only involve us in fresh and greater evils."

15 November, In his 'General Review of the Situation in the Two New Colonies', Lord Milner reports to Chamberlain, "... even if the war were to come to an end tomorrow, it would not be possible to let the people in the concentration camps go back to their former homes. They would only starve there. The country is, for the most part, a desert..."

16 November, On being questioned by St John Brodrick on his motivations for proposing the deportation of prominent Boer women, Kitchener cancels his orders.

21 November, Referring to a 'scorched earth' raid, Acting State President S.W. Burgers and State Secretary F.W. Reitz address a report to the Marquis of Salisbury, the British Prime Minister: "This removal took place in the most uncivilised and barbarous manner, while such action is ... in conflict with all the up to the present acknowledged rules of civilised warfare. The families were put out of their houses under compulsion, and in many instances by means of force ... (the houses) were destroyed and burnt with everything in them ... and these families among them were many aged ones, pregnant women, and children of very tender years, were removed in open trolleys (exposed) for weeks to rain, severe cold wind and terrible heat, privations to which they were not accustomed, with the result that many of them became very ill, and some of them died shortly after their arrival in the women's camps." The vehicles were also overloaded, accidents happened and they were exposed to being caught in crossfire. They were exposed to insults and ill-treatment by Blacks in service of the troops as well as by soldiers. "...British mounted troops have not hesitated in driving them for miles before their horses, old women, little children, and mothers with sucklings to their breasts ..."

30 November, The officially recorded camp population of the White camps is 117 974 and the deaths for November are 2 807.

1 December, Fully aware of the state of devastation in the Republics, and trying to force the Boer leadership to capitulate, Lord Milner approves a letter that Kitchener sends to London, with identical copies to Burger, Steyn and De Wet. In the letter he informs them that as they have complained about the treatment of the women and children in the camps, he must assume that they themselves are in a provision to provide for them. He therefore offers all families in the camps who are willing to leave, to be sent to the commandos, as soon as he has been informed where they can be handed over.

4 December, Lord Milner comments on the high death rate in the Free State concentration camps: "The theory that, all the weakly children being dead, the rate would fall off, it is not so far borne out by the facts. I take it the strong ones must be dying now and that they will all be dead by the spring of 1903! ..."

7 December, In a letter to Chamberlain, Lord Milner writes: "... The black spot - the one very black spot - in the picture is the frightful mortality in the Concentration Camps ... It was not until 6 weeks or 2 months ago that it dawned on me personally ... that the enormous mortality was not incidental to the first formation of the camps and the sudden inrush of people already starving, but was going to continue. The fact that it continues is no doubt a condemnation of the camp system. The whole thing, I now think, has been a mistake."

8 December, Commenting on the concentration camps, Lord Milner writes to Lord Haldane: "I am sorry to say I fear ... that the whole thing has been a sad fiasco. We attempted an impossibility - and certainly I should never have touched the thing if, when the 'concentration' first began, I could have foreseen that the soldiers meant to sweep the whole population of the country higgledy piggledy into a couple of dozen camps ... "

10 December, President Steyn replies to the British Commander-in-Chief Lord Kitchener's letter about releasing the women and children, that, however glad the burghers would be to have their relatives near them, there is hardly is single house in the Orange Free State that is not burnt or destroyed and everything in it looted by the soldiers. The women and children will be exposed to the weather under the open sky. On account of the above-mentioned reasons they have to refuse to receive them. He asks Kitchener to make the reasons for their refusal known to the world.

Anglo-Boer war prisoners in St Helena showing old men and young boys with toys made at the camp. Source: Parliament Archive

11 December, In his reply to Kitchener's letter about the release of women and children, Chief Commandant De Wet says: "I positively refuse to receive the families until such time as the war will be ended, and we shall be able to vindicate our right by presenting our claims for the unlawful removal of and the insults done to our families as well as indemnification on account of the uncivilised deed committed by England by the removal of the families ..."

12 December, The report of the Ladies Commission (Fawcett Commission) is completed on this day, but is only published during February 1902. The Commission is highly critical of the camps and their administration, but cannot recommend the immediate closure of the camps "... to turn 100 000 people new being fed in the concentration camps out on the veldt to take care of themselves would be a cruelty; it would be turning them out to starvation..." The Commission substantiated the most Emily Hobhouse's serious charges, bur reviled her for her compassion for enemy subjects.

22 December, On Peace Sunday, Dr Charles Aked, a Baptist minister in Liverpool, England, protests: "Great Britain cannot win the battles without resorting to the last despicable cowardice of the most loathsome cur on earth - the act of striking a brave man's heart through his wife's honour and his child's life. The cowardly war has been conducted by methods of barbarism ... the concentration camps have been Murder Camps." He is followed home by a large crowd and they smash the windows of his house.

31 December, The camp population in White camps is 89 407 with 2 380 deaths during December.

1902

22 January, In a daring exploit, General Beyers and about 300 men seize the concentration camp at Pietersburg and take the camp superintendent and his staff prisoner. After all-night festivities with wives, friends and family, the superintendent and his staff are released the next day on the departure of Beyers.

31 January, The officially reported White camp population is 97 986 and the deaths for January are 1 805.

4 March, The long-delayed report of the Ladies Commission (Fawcett Commission) on the concentration camps is discussed in the House of Commons. The Commission concludes that there are three causes for the high death rate: "1. The insanitary condition of the country caused by the war. 2. Causes within the control of the inmates. 3. Causes within the control of the administration." The Opposition tables the following motion: "This House deplores the great mortality in the concentration camps formed in the execution of the policy of clearing the country." In his reply Chamberlain states that it was the Boers who forced the policy on them and the camps are actually an effort to minimise the horrors of war. The Opposition motion is defeated by 230 votes to 119.

24 March, Mr H.R. Fox, Secretary of the Aborigines Protection Society, after being made aware by Emily Hobhouse of the fact that the Ladies Commission (Fawcett Commission) ignored the plight of Blacks in concentration camps, writes to Joseph Chamberlain, Colonial Secretary. He requests that such inquiries should be instituted by the British government "as should secure for the natives who are detained no less care and humanity than are now prescribed for the Boer refugees". On this request Sir Montagu Ommaney, the permanent under-secretary at the Colonial Office, is later to record that it seems undesirable "to trouble Lord Milner ... merely to satisfy this busybody".

9 April, Emily Hobhouse's 42nd birthday.

30 April, The officially reported population of the White camps is 112 733 and the death toll for April stands at 298.

15 May, Sixty Republican delegates take part in a three-day conference in Vereeniging, debating whether to continue fighting or end the war.Complicated negotiations continue between Boer delegates among themselves and British delegates, also with different opinions, up to the end of May.During the peace negotiations Acting President Schalk Burger of the ZAR (South African Republic/Transvaal) says: "... it is my holy duty to stop this struggle now that it has become hopeless ... and not to allow the innocent, helpless women and children to remain any longer in their misery in the plaque-stricken concentration camps ..."